Last positing in this thread: Visual Literary History (4)

Data http://positivists.org/r/simons-ESTC-1477-1800.xlsx, data extracted in 2001

The diagrams of this posting have started to circulate. The first was published in 2002 (at the Marteau website), the others had their first appeareances in the English Wikipedia article Term Catalogue and in the German Wikipedia articles Messkatalog and Aufklärung in 2010.

The graphs show a strong correlation between numbers of titles printed per year and changing political situations. They pose some more complex questions at second sight. One would need detailed paper consumption statistics to answer these questions.

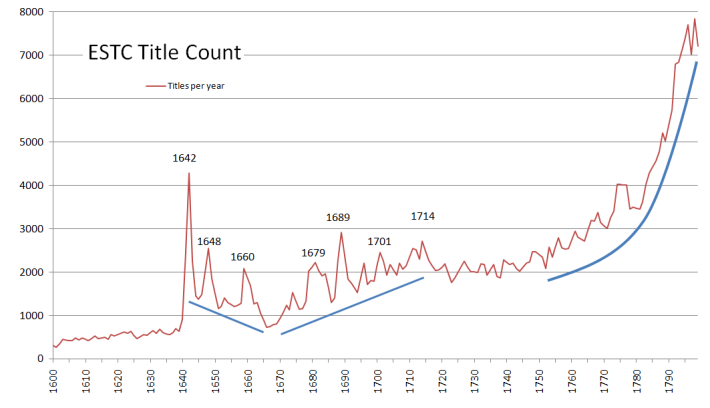

The data behind the graphs have been extracted from the ESTC in 2001 in rather tedious manual labour. Like the German VD16 and VD17 data (see the last posting) they needed a bit of further manipulation to eliminate the peaks of the “round” years (1660, 1670, 1680, etc) that are preferred as aproximate dates for undated materials. (I replaced these data, with the exception of the exceptional year 1640, with averages of the neighbouring years.) A “title” is for the editors of the ESTC an edition. The eight editions of Robinson Crusoe published in 1719 create eight ESTC-entries.

400 to 500 titles appeared in Shakespeare’s days per year in English and in the English speaking territories — an immensely stable production with a slow and gradual increase until the turbulences of the revolution of the 1640s. 694 titles were printed in 1638, 627 in 1639, but then 904 titles in 1640, 2464 in 1642, and 4279 in 1643, and a drop follows: 2244 titles in 1644, and so on.

The revolution came with press wars. The end of censorship through the Star Chamber in 1641 opened the gates for all ensuing turbulences. The graph is changing at this point from a rather stable line to one of sharp ups and downs. Instead of a 5 or 10 year trend line I inserted manual indications for the trends one would note with the historical background in mind. The years of the common wealth and the civil war (1640—1660) are marked by sharp peaks and by a gradual decline. The decline is only reversed after 1666. The Great Fire of London marks the deepest point in the development. 1648, the peace negotiations on the continent, and 1660, the restoration of Charles II incite floods of pamphlets; they all generated their individual peaks.

From the late 1660s to 1714 we get a steadily rising production with peak years of political interest: The Anglo-Dutch Wars (1665–67, 1672–74) fuelled debates, the “Exclusion Crisis” (1678 through 1681), the “Popish Plot” (1678) are discernible. 1688/89 are the years of the Glorious Revolution. William III dies in 1701; heated debates over the succession follow, the War Spanish of the Succession begins a year later; religious politics remain a topic with the Sacheverell Trial and the fall of the Whig Government (1709—1711). George I. ascends the English throne in 1714, a rebellion follows. We have from then onward, however, a rather stable phase, the Walpole era (1721—1742).

A second structural change appears in the 1750s. A new, almost exponential growth in title numbers sets in and goes through into the 19th century.

1640: From a market of books to a market of political and religious pamphlet wars

The book production did not make a 600% jump between 1639 and 1643. The amount of paper for such a jump was not available. Title counts are blind to what they count. A small tract of two pages will be a title just as a 600 page book. It is easy to print ten editions of a controversial pamphelt within a couple of weeks in an attempt to meet the demand and not to produce a single copy for the shelf. The title count will boost with such entries.

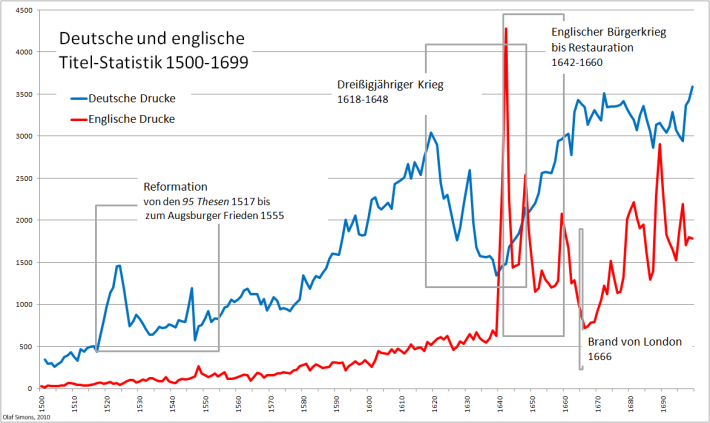

The numbers seem to support the thesis Habermas has discussed in his book on the critical public sphere in 1962: England was an early democracy and enjoyed critical exchanges at an early stage; things were presumably different on the continent where the censorship laws of all the petty monarchies and dukedoms were far stricter. A comparison of German and English statistics for the period 1500 to 1700 puts, however, a question mark behind any such statement. The English press was a late comer — the German territories were the first to use the press in propaganda wars:

The English title-output was comparatively small before the 1640s. The German territories had far more printing presses to satisfy the demand in the numerous cultural centres, even if such “centres” were small towns of 15,000 inhabitants such as Gotha. The German territories had, at the same moment, developed a sophisticated distribution system with the two yearly fairs of Frankfurt and Leipzig.

The German speaking territories might not have enjoyed more liberal press laws. The market, however, did not care. The fragmented confessional and political map allowed the printing of books on routes of evasion: One printed in neighboring territories; publishers were ready to sell dangerous materials without imprint information and claimed they had bought these titles at the fairs. Germany reached a free press with heated press wars at the beginning of the 1520s, more than a hundred years before the English.

The late 18th-century rise — a phenomenon of complex dimensions

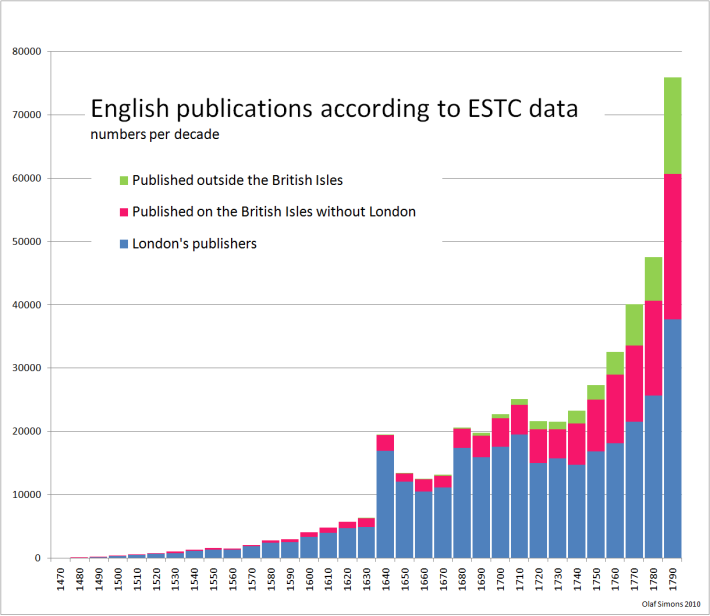

The late 18th-century development is difficult to explain. One would love to know what exactly created this rise. For the following diagram I worked with data for decades (instead of years) to allow a basic sub division of publishing places. A growing production could only be sold on a growing market, so my assumption. Three options should, however, be explored for the clearer picture and cannot be explored that easily at the moment:

- more people could read (and had the money to buy printed materials)

- new materials were printed for the wider market — the most likely candidate is here the fictional production that begins to sell under the label of “literature” (thus far the term for academi publications) in the course of the 1750s

- new markets emerged: those of provincial cities and the colonies

All three factors will be equally valid. The following diagram is compiled to substantiate the third claim. The English market was basically London’s book market far into the 18th century. Dublin was a rival with frequent “Dublin piracies”. Glasgow, York and Edinburgh had their own printing presses but used them rather for cheap materials that went into the local distribution. Oxford and Cambridge, the two university cities, remained of marginal importance on the national market based in London. London developed a production of politics and theology. Both fields prospered in political battles. The belles lettres, a market of elegant books added to London’s production (another posting will give statistics).

The graph shows that this situation changed only in the course of the 18th century with publishers outside London catching up. North America began to generate its own market in the 1770s. New publishers began to serve these new regional, national and local audiences, so the graph.

It is difficult to get a more precise picture for the second assumption: A new field of “literature” is emerging after 1750 (my present book project deals with this Thesis). We would need divisions of the entire market, divisions that give 100% cross sections for each year and decade in order to prove such an assumption (titles that are listed in more than one category make it difficult to offer such 100% cross-sections at the moment).

Deficits: One would need statistics of the paper consumption

The diagrams collected in this posting are obviously significant. They offer graphs for title outputs and show structural changes here: Markets changed where politics allowed these changes. The press was used in press wars on the continent as early as the 1520s, in England only after 1640. One would print hundreds of pamphlets in the heated debates of the reformation in Germany. The British peaks are sharper as we are dealing here with peaks on a small political ground: All debates London could produce were automatically national debates and vice versa. The German production was one of numerous regional centres. Larger Trends are here only visible if the affect all the territories — the reformation, the Thirty Years war have such effects.

We have problems to get a better picture of the late 18th-century rise in title-production numbers. A title is in all these statistics just a title — it can be a book of 600 pages and 800 copies or a pamphlet of two pages that needed to be reprinted ten times before the demand was met. The ESTC, as its German sister projects, lists individual print runs, every edition is counted. A two page pamphlet printed in ten print runs gives ten entries, the single book of far wider implications just one.

A special problem has not been mentioned thus far: The catalogues I exploited for these diagrams avoid the periodical production. How many “titles” is a newspaper of 156 copies per year that runs through a century? If we are happy it is at least one title, if not the paper will not be listed. The same goes for journals: Is a journal of 12 issues per year printed that is printed through a century just one title? or is it 1,200 titles? Our bibliographies focus on the book production and avoid these titles.

One would need statistics of the paper consumption to offer more significant diagrams. The early modern audience read newspapers, and after the 1680s: a rapidly growing number of journals.

We need to know how much paper went into short political tracts, how much went into book? how much went into newspapers and journals. The entire amount of paper processed by the printing presses is the ideal indicator to understand what people were actually reading.

What could we do in order to arrive at statistics of the paper consumption? We do not know the print runs of early modern materials, we do not have enough data of publishers to see what amounts of paper they actually invested into the different fields of the production.

And yet we could reach a tentative picture: The present online catalogues — the ESTC, the VD16, the VD17, the STCN — offer the data we would need in order to give sound estimates. All the titles are already equipped with format information (folio, quarto, octavo etc.); we get page numbers. If we assume that titles received average editions of 500 to 1,000 copies we can combine these data and estimate how much paper the individual print run required.

One would not want do give manual computations, one would want to have automatic computations; and of course, it would be nice if catalogues like the ESTC, the VD16, VD17, VD18 and the STCN could offer statistics as search result: timelines, cross sections in pies, distributions on maps.

An additional posting on the need of paper statistics.

Pingback: 5: Easy to get but dangerous: title statistics. Book historians need graphs of the paper consumption. | critical threads